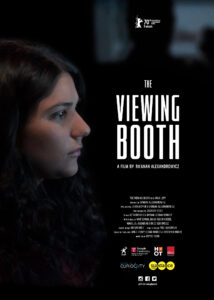

Prior to World War I a friend writes to Virginia Woolf asking about how to prevent the coming  war. She replies… by asking him about the definition of we. When we look at a series of photographs, do we see the same thing? THE VIEWING BOOTH recounts a unique encounter between a filmmaker and a viewer — exploring the way meaning is attributed to non-fiction images in today’s day and age. In a lab-like location, Maia Levy, a young Jewish American woman, watches videos portraying life in the occupied West Bank, while verbalizing her thoughts and feelings in real time. Maia is an enthusiastic supporter of Israel, and the images in the videos, depicting Palestinian life under Israeli military rule,

war. She replies… by asking him about the definition of we. When we look at a series of photographs, do we see the same thing? THE VIEWING BOOTH recounts a unique encounter between a filmmaker and a viewer — exploring the way meaning is attributed to non-fiction images in today’s day and age. In a lab-like location, Maia Levy, a young Jewish American woman, watches videos portraying life in the occupied West Bank, while verbalizing her thoughts and feelings in real time. Maia is an enthusiastic supporter of Israel, and the images in the videos, depicting Palestinian life under Israeli military rule,  contradict some of her deep-seated beliefs. Empathy, anger, embarrassment, innate biases, and healthy curiosity — all play out before our eyes as we watch her watch the images created by the Occupation. As Maia navigates and negotiates the images, which threaten

contradict some of her deep-seated beliefs. Empathy, anger, embarrassment, innate biases, and healthy curiosity — all play out before our eyes as we watch her watch the images created by the Occupation. As Maia navigates and negotiates the images, which threaten  her worldview, she also reflects on the way she sees them. Her candid and immediate reactions form a one-of-a-kind cinematic testimony to the psychology of the viewer in the digital era. THE VIEWING BOOTH is director Ra’anan Alexandrowicz (The Law In These Parts) joins us for a in-depth conversation regarding his inspiration and his motivation for creating a rigorous social / cultural / political evaluation of the way in which people take in, process and contextualize image-based information and how they see the world around them.

her worldview, she also reflects on the way she sees them. Her candid and immediate reactions form a one-of-a-kind cinematic testimony to the psychology of the viewer in the digital era. THE VIEWING BOOTH is director Ra’anan Alexandrowicz (The Law In These Parts) joins us for a in-depth conversation regarding his inspiration and his motivation for creating a rigorous social / cultural / political evaluation of the way in which people take in, process and contextualize image-based information and how they see the world around them.

Download MP3 Podcast | Open Player in New Window

For news and updates go to: theviewingboothfilm.com/en/the-film

Director’s Statement – During the time of the Spanish Civil War, Virginia Woolf received a letter from a prominent lawyer in London who asked her, perhaps provocatively: “How, in your opinion, are we to prevent war?” In her answer Woolf suggested they first address his use of the word “we” with a little thought experiment. What would happen, she asks him, if they both observe the images of war that are published every week? “Let us see,” she writes, whether when we look at the same photographs, we will feel the same things.” I consider my first encounter with this correspondence, around five years ago, as the moment in which the film The Viewing Booth was conceived. Woolf’s simple and prophetic words were written in a time when the photography of human suffering was a nascent and seemingly unshakable medium of truth. Reading them 80 years later, in a time when truth itself is a contested term in public life, I asked myself: Are people who are looking at the images I make, seeing what I am seeing? Woolf’s words permitted me, or rather commanded me, to question the way nonfiction images function, especially in regard to their role in advocating human rights and social justice. For a few years I searched for the cinematic way to do this. If documentaries are an exploration of reality, I thought, then there must be a way to explore the reality that is the documentary. The more I searched for the filmic path to do this, the more I felt that in order to understand images I should stop looking at images, but rather turn the camera towards the viewers. The result is The Viewing Booth. While it encompasses questions that were cultivated over a long period of time, The Viewing Booth finally happened, almost by chance, during a session that was meant to be a pilot shoot, testing a possible concept for the project. Years of thoughts suddenly and unexpectedly found a cinematic expression when Maia Levy, whom I had never met before, entered the improvised viewing booth that I had created at Temple University in Philadelphia. Maia’s dialogue with the images of Palestine and Israel, as well as her reflections on her own perception of these images, lead me to confront myself — as an image maker — in ways that I had not expected. The result is an intimate and tightly focused film that invites viewers to delve into quintessential universal questions on the perception of nonfiction images in our times. The introspective nature of The Viewing Booth determined its unconventional form and structure – one that often evokes the idea of a mirror, or a hall of mirrors. As the work on the film progressed, I realized that it is not only Maia and myself, who are facing our own reflections through this film. If it achieves its objective, The Viewing Booth will become a mirror for its viewers, as well as for the nonfiction tradition – a tradition which I consider myself a part of. – Ra’anan Alexandrowicz

About the filmmaker – Ra’anan Alexandrowicz is best known for the documentary The Law in These Parts (2011), which received the Grand Jury Award at the Sundance Film Festival, a Peabody award, and numerous other prizes. His earlier documentaries, The Inner Tour (2001) and Martin (1999), were shown in the Berlin Int’l Film Festival and MoMA’s New Directors/New Films. Alexandrowicz’s single fiction feature, James’ Journey to Jerusalem (2003), screened in Cannes Directors’ Fortnight and at the Toronto Int’l Film Festival and received several major awards. His films have been released theatrically in the U.S. and Europe, and broadcast by PBS, BBC and ARTE, as well as other television channels.

SOCIAL MEDIA

facebook.com/TheViewingBooth

twitter.com/TheViewingBooth

instagram.com/theviewingbooth

@TheViewingBooth

#Berlinale2020

“An outstanding probe into not just how people think about a conflict in the Middle East, but the limits of nonfiction films regarding their ability to persuade and explore reality as it is — and whether such a thing is even possible.” – Alissa Wilkinson, Vox

“One of the most provocative of the films at True/False… this film speaks

not only to issues but to the function of documentary itself.” – Pat Aufderheide, Documentary Magazine

“Not just a valuable crash course in digital-age hermeneutics, this is a gauntlet thrown down to film-makers with an old-fashioned belief in the truth.” – Phil Hoad, Guardian

“‘The Viewing Booth’ stood out as one of the [Berlin] festival’s best documentaries… a meditation on the power of images to convey reality and influence systems of belief.” – A.J. Goldmann, Tablet Magazine